Let's Talk

Request a private consultation. Discover how you can Make Your Move™.

Despite best intentions, M&A dealmakers can fall victim to traps that lead to value destruction.

Mergers & acquisitions (“M&A”) refers to the buying/selling of a business. Mergers & acquisitions always involve combining two separate companies. These companies can be both private and public. M&A can take place by:

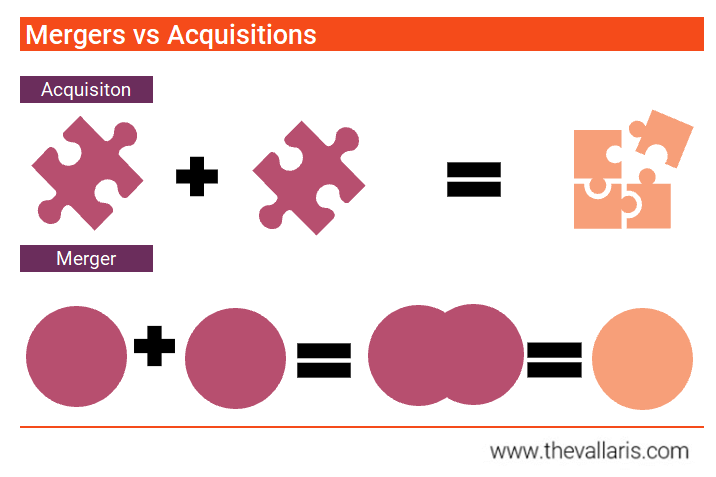

A merger is the combination of two companies to form one. Both companies agree to combine when they are roughly the same size, have the same strategic goal and feel that they are better collaborating rather than competing. An acquisition occurs when one company takes over the other.

exhibit 1: mergers vs acquisitions

Merger

Legally speaking, in a merger two companies consolidate into a new entity with a new ownership and management structure (with employees from the purchaser and seller). A more common distinction to differentiating the deal is whether the purchase is friendly (merger) or hostile (acquisition). Mergers require no cash to complete but dilute each company’s individual power.

In practice, a friendly merger of equals is rare. It’s hard to imagine that two CEOs from different companies would agree to give up some authority to realize the benefit from combining companies. Should this happen, the shares of both companies are surrendered, and new shares are issued under the name of the new business identity.

Typically, mergers are done to reduce operational costs, expand into new markets, boost revenue and profits. Mergers are usually voluntary and involve companies that are roughly the same size and scope.

Due to the negative connotation, many acquiring companies refer to an acquisition as a merger even when it is clearly not.

Acquisition

In an acquisition, a new company does not emerge. Instead, the smaller company is often consumed and ceases to exist with its assets becoming part of the larger company. Acquisitions, sometimes called takeovers, generally carry a more negative connotation than mergers. As a result, acquiring companies may refer to an acquisition as a merger even though it’s clearly a takeover. An acquisition takes place when one company takes over all of the operational management decisions of another company. Acquisitions require large amounts of cash, but the buyer’s power is absolute.

The two terms have become increasingly blended and used in the same breadth since mergers are uncommon and takeovers are viewed in a negative light. A corporate consolidation/restructuring of companies or assets may be described today as a M&A transaction when in fact is it either a merger or acquisition. The practical differences between the two terms are slowly being eroded by the new definition of M&A deals.

The main purpose of M&A activity is to accelerate business growth. Both acquisitions and mergers allow a business to grow at a rate that would not be possible through organic growth. Organic growth refers to internal growth from a business’ operations, often measured by year-on-year sales. Inorganic growth is growth from buying other businesses.

Inorganic growth can help immediately increase market share, revenues and assets. Other common benefits include:

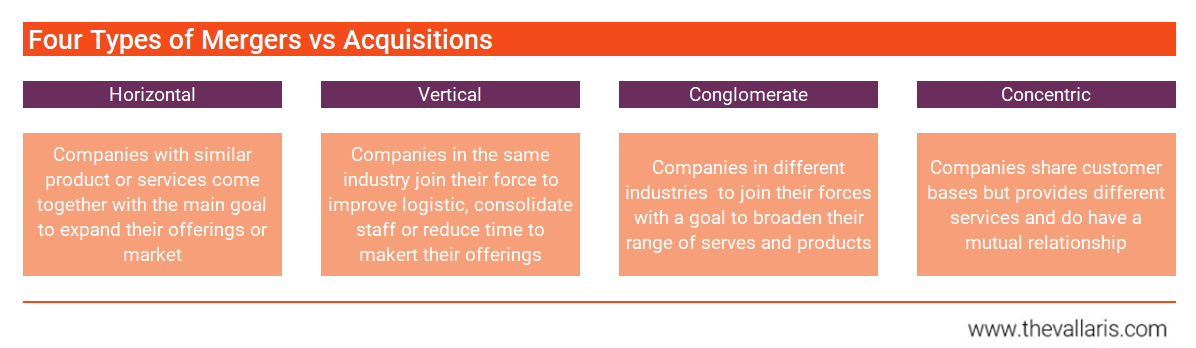

exhibit 2: merger vs acquisition types

There is always synergy value created by the joining or merger of two companies. The synergy value can be seen either through revenues (higher revenues), expenses (lowering of expenses) or the cost of capital (lowering of overall cost of capital).

Many deals can be closed with a buyer, a seller and just a financial adviser and lawyer. At the other extreme, consummating a large, multi-jurisdictional, public merger may involve dozens of parties, from multidisciplinary groups of parties’ own internal personnel to financial advisers, lawyers in various countries and states, regulatory, environmental, human resources (HR) and antitrust specialists, proxy solicitors, escrow agents, financing sources, insurers and even lobbyists.

Key participants include:

Purchaser

Every M&A transaction involves at least one purchaser, or buyer. This is the party making the acquisition. This is the person (i.e., individual or company) that signs the purchase agreement, pays the purchase price and which, after closing, directly or indirectly, owns or controls the target company or its assets. The purchaser discusses with the seller or target to establish the primary financial and strategic terms of the transaction. He/she also engages a financial advisor (buy-side) to lead negotiations of key deal points, manage operational and financial due diligence and select and supervise transaction advisers, which includes an assortment of accountants, corporate bankers. lawyers, and others.

While the purchaser often is the ultimate parent company involved in the transaction, it need not be. In fact, it frequently isn’t. Instead, a company may also consummate an acquisition using use an existing operating subsidiary or form a new company altogether. This may be done for a variety of reasons, including for operational, tax, regulatory and risk mitigation benefits.

Seller

This is the person or persons selling the shares or assets and liabilities to the purchaser. Unlike the purchaser, every deal does not necessarily involve a seller acting as a deal participant. For example, in transactions where the target is a publicly-traded company, although public shareholders are effectively selling the company and, accordingly, may be thought of as the sellers, the Board of Directors and management of the target company itself usually take on the role that would be played by a seller in a private deal.

In private M&A transactions, where there is typically one or a small group of individuals who control the target company, these ‘control persons’ are the seller. In that capacity, as the counterpart to the purchaser, they sign the purchase agreement, receive the purchase price and transfer the shares or assets subject to the deal. He/she also engages a financial advisor (sell-side) to negotiate with the buyer to establish the primary financial and strategic terms of the transaction, provide information to the purchaser and its advisers conducting due diligence and select and manage its own set of transaction advisers.

Importantly, the seller in a private M&A transaction is also responsible for post-closing warranty and indemnification obligations owed to the buyer (i.e., obligations to reimburse the buyer for certain losses it may incur as a result of the sale and purchase agreement (“SPA”) breaches).

As with the purchaser, a seller’s entity may not be an operating company with substantial assets at the top of its organizational hierarchy. Quite often, the seller entity is a holding vehicle or operating subsidiary owned or controlled by one or more other companies. In these cases, seller parent companies may be expected to guarantee post-closing obligations of the seller, including indemnification obligations.

Target

This refers to a company, as opposed to assets, whose ownership or control is to be acquired in the M&A transaction. It may refer not either the subject of a private M&A transaction or a public deal. The term is not used in transactions involving a sale of assets and liabilities instead of shares. In an acquisition of business assets, the terms “Acquired Assets” and “Assumed Liabilities” are used instead.

In a private deal, the target company itself may not be expected to participate actively in the negotiation and implementation of the transaction, aside from facilitating the buyer’s due diligence by providing access to information and materials. After all, a private M&A target is the subject of the deal and not usually a party to it. As mentioned above, this differs somewhat from the public M&A context, where the target company’s Board and management serve as representatives of the interests of public shareholders and the public company target is typically a party to the principal transaction agreements. In that case, the target plays the role of the seller.

Target board of directors

A company’s Board of Directors owe fiduciary duties to the company’s shareholders. This means directors act for the benefit of the shareholders, while subordinating their own interests. In an M&A transaction that has either a diffuse shareholder base and/or there is a potential conflict of interest impacting a controlling shareholder, these fiduciary duties require the target’s Board of Directors (or a committee comprised of disinterested directors) to participate actively, or manage, the M&A transaction process on behalf of the target company. They may do so using their own independent financial and legal advisers. They may also rely upon target company management in discharging their duties.

In most private deals, however, target Board fiduciary duties may not even be relevant. Most non-asset private M&A transactions are structured as share purchases, which means the buyer acquires control of the target by negotiating directly with the shareholders. In that situation, because shareholders are making their own choices, target company directors aren’t being called upon to take any action on behalf of the company. In fact, the target Board need not even approve the transaction.

Financial advisers (sell-side)

Also called investment bankers if they are bank employees instead of employees of an advisory firm. They provide financial and strategic advice to target companies and sellers. On sell-side engagements, they are usually the first advisers contacted at the commencement of a potential transaction and will advise management and the Board as to deal strategy, potential buyers, timing and the process for marketing the transaction, among other things. They frequently serve as the primary points of contact for possible buyers, prepare information memos, perform financial modelling, organize auctions, analyze competing bids, and lead negotiations on deal terms and structure. Critically, they may assist target company Boards of Directors in discharging their fiduciary duties by rendering fairness opinions, which speak to the fairness, from a financial point of view, of the transaction consideration to the target company shareholders.

Financial advisers (buy-side)

In buy-side engagements render reciprocal services for M&A buyers, including reviewing the business case, identifying acquisition targets, financial modelling, preparing valuations, risk spotting, leading negotiations, communicating with sell-side investment bankers and rendering tactical advice. They may also assist buyers in obtaining M&A financing or even provide it themselves.

Other advisers

A number of additional advisers may be brought as depending on the complexity of the deal a hand. These include:

exhibit 3: five steps in a mergers & acquisitions

1. M&A strategy: The purchaser performs a business case review of its business. Growth options should discuss when M&A should be used.

exhibit 4: setting mergers & acquisitions criteria

2. Screen targets: Scan and identify takeover candidates. Qualify targets that may have a good strategic fit for the purchaser.

3. Valuation and due diligence: Value the price range to be paid of the target once an appropriate company is shortlisted through primary screening. Perform detailed analysis of the target company, i.e. due diligence.

4. Pre-close planning: Negotiate through signing to acquire the target. Once the target company is selected, the next step is to start negotiations. The aim is for both companies to agree to the deal for benefit of both their businesses and shareholders.

5. Post-merger integration: If all the above steps fall in place, both the participating companies announce the merger or acquisition.

Valuation is independently conducted by both purchase, as well as the target. The purchaser aims to purchase the target at the lowest price, while the target intends to secure the highest price.

Valuation is an important part of M&A, as it guides the purchaser and seller to reach the final transaction price. Three major valuation methods that are used to value the target are:

Discounted Cash Flow (“DCF”) Method: The target’s value is calculated based on its future cash flows.

Guideline Public Company/Transaction Method: Relative valuation metrics for either public companies and/or transaction are used to determine the value of the target.

Adjusted Net Asset Method: Each asset and liability on the target’s balance sheet is adjusted from book value to fair value.

For a more detailed discussion on this topic, please refer to our business valuation page.

One word differentiates M&A valuation from standalone valuation: synergies. An M&A valuation involves two steps: valuing the target on a standalone basis and valuing the potential synergies of the deal.

exhibit 5: mergers & acquisitions value waterfall

When it comes to valuing synergies, there are two types of synergies to consider: revenue and cost. Cost synergies, also called operating or operational synergies, refer to direct cost savings to be realized after completing the merger and acquisition process. These are benefits that are virtually sure to arise from the merger or acquisition – such as payroll savings that will come from eliminating redundant personnel between the purchaser and target companies.

Revenue synergies are revenue increases that the purchaser hopes to realize after the deal closes. These are also know as soft synergies as these benefits is not as assured compared to hard synergies.

No growth strategy: When purchasers have not laid out a growth strategy for their business. They are not crystal clear about how the mission of an M&A deal and help them achieve their corporate vision.

Poor strategic fit: When both companies have a divergent views on business objectives and strategies.

Poorly managed integration: Integration that is poorly managed in terms of design, resourcing, timing and executing and leads to implementation failure.

Incomplete due diligence: Inadequate due diligence can lead to failure of M&A since key risks and deal breakers are not identified and mitigated.

Aggressive business valuation: Optimistic financial projections by the target company leads to overpayment and under delivery of results.

It takes a lot for two previously independent business to join forces, agree on prices and strategy, identify and extract revenue and cost synergies, and maintain employee productivity. It is not unreasonable to compare the process to trying to put together a 1,000-piece puzzle, except that your right and left hands have never worked together before.

An M&A process will typically take anywhere from six months to several years, depending on the complexity of the deal. While it can be helpful to draft a timeline and target a closing date for tracking purposes, understand that delays are inevitable, so build in time for change.

M&As are important change agents and a critical component of any business strategy. The fact is that with businesses evolving at an ever blistering pace, only the most innovative and nimble can survive. That is why, it is an important strategic call for a business to consider M&A in their growth strategy. On a lighter note, M&A is like an arranged marriage, where partners will take time to understand, mingle, and decide if they are better off facing off industry competition together rather than apart.

Avoid the odds of destroying shareholder wealth in a bad marriage.

Request a meeting with VALLARIS.

[1] The Big Idea: The New M&A Playbook,” Clayton M. Christensen, Richard Alton, Andrew Waldeck, Harvard Business Review, March 2011.